Venue: Oddball Films, 275 Capp Street, San Francisco

Date: Saturday, December 3, 2011 at 8:00PM

Admission: $10.00 - Limited Seating RSVP to programming@oddballfilm.com or 415.558.8117

Program Features:

Song of Ceylon (1934, B+W)

The first part of the film depicts the religious life of the Sinhalese, interlinking the Buddhist rituals with the natural beauty of Ceylon. Opening with a series of pans over palm leaves, we then gradually see people journey to Adam's Peak, a centre of Buddhist pilgrimage for over two hundred years. This is continually intercut with images of surrounding natural beauty and a series of pans of a Buddhist statue. Part two focuses on the working life of the Sinhalese, again continually stressing their intimate connection to the surrounding environment. We see people engaging in pottery, woodcarving and the building of houses, whilst children play. The third part of the film introduces the arrival of modern communications systems into the fabric of this 'natural' lifestyle, heralded by experimental sounds and shots of industrial working practices. Finally, in the last part of the film, we return to the religious life of the Sinhalese, where people dress extravagantly in order to perform a ritual dance. The film ends as it began, panning over palm trees.

Made by the GPO Film Unit and sponsored by both the Empire Tea Marketing Board and the Ceylon Tea Board, Song of Ceylon is one of the most critically acclaimed products of the documentary film movement. It was hailed at the time of its release by author and film critic Graham Greene as a cinematic masterpiece, and received the award for best film at the International Film Festival in Brussels, 1935.

The film is a sophisticated documentary, notable for its experimentation with sound. It features crucial input from Brazilian Alberto Cavalcanti, who helped with the soundtrack, as well as composer Walter Leigh, who experimented in the studio to create a number of sound effects.

The film's soundtrack was carefully put together in a studio because technical limitations precluded the ability to record synchronized sound. Leigh constructed a number of 'exotic' sounds, reflecting ceremonial practice and interweaved them with anthropological narration. At times these sounds are disconcerting in the way that they are used: gong sounds, for instance, are treated and manipulated to increase their harshness. The most striking use of experimental sound occurs in the third section of the film, which depicts the effects of telecommunications systems on the native lifestyle. A montage of industrial sounds and electronic waves are mixed together, creating an expressive, yet rather dissonant, sense of the encroachment of modernity.

The third section of the film is the most disconcerting of the four sections and initially contrasts with the other sections. Yet overall the film is structured in a 'circular' manner, emphasizing that continuity can occur despite the onset of an initially alien way of life. The first two sections focus on native rituals and working practices, always stressing the Sinhalese in relation to their natural environment. The modernity of the third sequence initially implies that nature and tradition are endangered by advanced industrialism, but in the last section we return again to the natives partaking in another ceremony, while industrial sounds become merged with the 'traditional' sounds.

Ultimately, then, Song of Ceylon imparts the message that nature and native traditions can coexist harmoniously with modernity. The film proposes a benign, rather than ruthless, message of progress, stressing the benefits of technological innovations. At the end of the film, the camera pans over palm leaves, while a gong sound is also heard, reprising images and sounds featured at the start.-Jamie Sexton

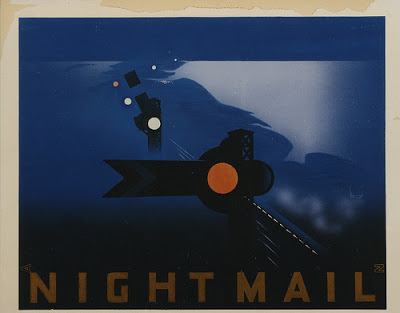

Night Mail (1936, B+W)

Night Mail is one of the most critically acclaimed films to be produced within the British documentary film movement. It was also among the most commercially successful, and remains the film most commonly identified with the movement. By 1936, film output at the GPO Film Unit was divided between the production of relatively routine films promoting Post Office services, and more ambitious ones experimenting with the use of sound, visual style, narrative and editing technique. Night Mail is firmly in the latter category.

Although it was primarily directed by Harry Watt, Basil Wright developed the script, and had overall production responsibility for the project. The resulting film was edited by Wright and Alberto Cavalcanti; John Grierson and Stuart Legg were also involved in its production. The music score was arranged by Benjamin Britten and Cavalcanti, and the rhyming verse used in the film - spoken by Pat Jackson - was written by W.H. Auden, who also acted as assistant director.

Night Mail is an account of the operation of the Royal Mail train delivery service, and shows the various stages and procedures of that operation. The film begins with a voiceover commentary describing how the mail is collected for transit. Then, as the train proceeds along the course of its journey, we are shown the various regional railway stations at which it collects and deposits mail. Inside the train the process of sorting takes place. As the train nears its destination there is a sequence - the best known in the film, in which Auden's spoken verse and Britten's music are combined over montage images of racing train wheels.

Although the narrative is concerned with issues of national communication and integration, the thematic centre of the film is more closely linked to representations of the regional environment. This elevation of the regional above the national is reinforced by the portrayal of the railway as separate from the metropolitan environment, and little attempt is made to link the railway and its workers with the city. The film also channels representations of modern technology and institutional practice away from an account of the industry of postal delivery, and into a study of the train as a powerful symbol of modernity, in its natural element speeding into the countryside.- Ian Aitken

Documentary, public information film, morale booster; propaganda film - these are descriptions that could be applied to many of the 10 to 20 minute shorts that flourished and reached a peak of expression in the 1930s and '40s. Humphrey Jennings' films covered the whole of the Second World War in Britain. His quiet, emotive style produced some of the most memorable film images of the War; those from London Can Take It (1940), Listen To Britain (1942) and Fires Were Started (1943). Those titles, for the GPO and Crown Film Unit, were American funded and produced for American and British release.

Listen To Britain's title might suggest a strong sound element. There are the very recognizable sounds that one might expect in a wartime film: the evocative thunder of the 1000 horse power Rolls Royce Merlin engines of Spitfires and Lancasters, the cacophony of wartime heavy industry - tank factories, steel works, steam trains - but also the sounds of music; the egalitarian free classical music concerts, and radio; Workers' Play Time, musicians, Flanagan and Allen performing live at a lunchtime factory concert.

But it is the images, particularly the studies of people that are the real star. The gaunt, tired faces in this most desperate part of the war seem only slightly aware that Jennings' camera is there. In a factory, a young woman handles heavy precision metal drilling/cutting machinery, almost in a trance, her body and hands skillfully heaving the heavy equipment into precise position. At a concert, another young woman, standing against the wall alone, stares through or past the camera. She is defiant, self-assured, and independent. We know with hindsight that in the comparative austerity and repression of the immediate postwar period, women would not enjoy the same limited equalities, liberty and sexual freedom that they did in the war.

The editing in Listen To Britain is trademark Jennings: simple comparisons between scenes from everyday life and the manic, unreal struggle of the war effort. -Ewan Davidson

The Oil in Your Engine (1969) a technologically innovative film about the properties of oil in automotive engines produced by the makers of the biggest petroleum disaster in history-British Petroleum. The psychedelic visuals and experimental soundtrack, combined with the innovatively framed shots makes their “science” of oil lubrication all the more bizarre. Nominated for a BAFTA award (British Academy of Film and Television Arts).

About the GPO Film Unit

The post office film unit established by Sir Stephen Tallents in 1933 will be forever associated with John Grierson and his idea of documentary cinema. During his spell in charge (1933-1937), Grierson oversaw the creation of a film school that he attempted to direct towards a socially useful purpose. J. B. Priestley remembered, "if you wanted to see what camera and sound could really do, you had to see some little film sponsored by the post office or the Gas, Light & Coke company."

This early strand of the GPO Unit's filmmaking is best represented by its 'masterpiece', Night Mail (1936), which borrowed from the aesthetics of Soviet cinema to turn an explanation of the work of the travelling post office into a hymn to collective labou\r. To quote Priestley again, "Grierson and his young men, with their contempt for easy big prizes and soft living, their taut social conscience, their rather Marxist sense of the contemporary scene always seemed to me at least a generation ahead of the dramatic film people."

However, the significance of Grierson's project at the GPO Film Unit would be more apparent in its eventual influence than its immediate impact. What is perhaps more important to stress is that this idealistic strand was not the only or, perhaps, even the most important part of its work.

The GPO Film Unit had been established as part of the post office's new public relations department. It was a typically experimental move. For much of the interwar period, the GPO was the largest employer in Britain: it had around a quarter of a million employees and was at the cutting edge of business organization and technological research. Thus, for example, massive government investment in the telephone network saw the production of instructional films such as Telephone Workers (1933), an early attempt to help train a large staff that was spread over several geographically distinct sites.

As well as creating a national communications infrastructure, the GPO was attempting to introduce commercial ideas of customer service into what was then a government department. Thus one job of the GPO Film Unit was to find ways to bridge the gap between the stern norms of communication in the Civil Service and popular understanding. The serious impulse behind entertaining musical fantasies like The Fairy of the Phone (1936) was an attempt to find new ways to communicate with the public. This was an essential requirement if you believed, as Stephen Tallents, the GPO's Head of Public Relations did, that popular expectations of government were evolving. As he put it, the idea of government as being negative was being superseded by the idea that government should be positive, moving from "the preventing of the bad to the encouraging of the good".

The work of experimental artists and filmmakers such as Lotte Reiniger, Norman McLaren and Len Lye can, then, be understood as part of a wider GPO project, exemplified by Giles Gilbert Scott's Jubilee Telephone Kiosk and the development of services such as the Speaking Clock and '999', to move government into closer and more harmonious contact with the British people.

First and foremost, the Film Unit was responsible for promoting the reputation of the GPO, emphasizing the scale and success of its technological ambitions. This task informed the bombast of films like the comparatively big budget BBC - The Voice of Britain (1935), as well as the internationalist idealism of We Live in Two Worlds (1937), which envisaged how new communications technology would herald the coming of a global civilization. This thematic technophilia was also reflected in the Unit's method, especially in the sound experiments organized by the Brazilian émigré Alberto Cavalcanti. Among the GPO's sonic achievements was the first use of recorded speech (6.30 Collection, 1934), modernist experiments in sound montage (Song of Ceylon, 1934) and the employ of now feted composers such as Benjamin Britten, Maurice Jaubert and Darius Milhaud.

This characteristic of the Unit's work became more evident after Grierson was replaced by Cavalcanti and a theoretical approach to 'realism' became less important than developing a variety of inventive and colloquial idioms. At the most obvious level, the Unit pursued celebrity endorsements - persuading cricketer Len Hutton and family to appear in What's On Today (1938), for example - but this approach also began to prompt interesting experiments in film form.

Harry Watt's The Saving of Bill Blewitt (1936) is often referred to as the first 'story documentary'. The film combined real locales and non-professional actors with a narrative based script. Let off the leash by Cavalcanti, Watt began consciously to blend the aesthetic and social commitment of the early Grierson documentaries with narrative devices borrowed from Hollywood. This resulted in the GPO's most theatrically successful production, North Sea (1938), which wore its 'educational' brief more lightly and made an overt attempt to entertain. According to Denis Foreman's memoir, such fusions later fascinated the Italian Neo-Realists.

Cavalcanti's reign also saw the production of Humphrey Jennings' masterful Spare Time (1939), an imaginatively edited catalogue of working-class Britain at play. Playful and humane, Jennings' delightfully undidactic film was exhibited at the New York International Exhibition of 1939 as an example of an emerging 'new Britain.'

On the outbreak of the Second World War, the GPO Film Unit became the Crown Film Unit, and its morale-boosting mode was effectively nationalized, a move which resulted in the production of patriotic wartime classics such as London Can Take It (1940), Target for Tonight (1941) and Listen to Britain (1942). Now led by the sensitive producer, Ian Dalrymple, this was perhaps the Unit's most triumphant phase, ironic considering the amount of governmental opposition that Tallents and the Film Unit had faced in peacetime.

Although the GPO Film Unit was eventually subsumed by the newly created Central Office of Information in 1946, and many of the filmmakers from its golden age migrated into commercial film production and television, the post office continued to make films. Early GPO efforts like Cable Ship (1933) and Under the City(1934) had found their audience among children and in the provincial village halls of various voluntary organizations; later post office films concentrated on these more narrowly defined educational purposes. Indeed, later children's programs such as Postman Pat were arguably the long-term result of the public affection for the post office which the GPO Film Unit had been established to embed some 50 years earlier.-Scott Anthony